In this four part series, Janna Pate explores the Rites of Passage work at Pacific Quest. From “Huli Ka’e,” the Rites of Passage experience that students participate in, to the “Staff Vision Fast,” a unique opportunity for staff to gain personal and professional development and a deeper understanding of this important component of the Pacific Quest curriculum. Part I discusses Rites of Passage at Pacific Quest and Part II introduces what we call “Intent Statements “.

By: Janna Pate, Academic Coordinator

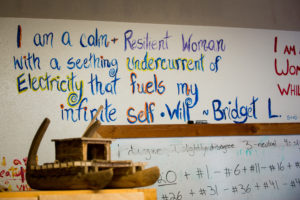

When I entered the fast, the Intent Statement I began with was: “I am unafraid of who I am and how I love this world.” This was the statement I brought with me to the group for feedback in a process called Intent Council.

Students at Pacific Quest also participate in Intent Council. This happens during their experience on Huli Ka’e. As a guide and later as a program supervisor, Intent Council was always my favorite group to witness and participate in. It takes a lot of courage to engage in this process.

During Intent Council, students are asked to follow a set of guidelines developed through the work of The Ojai Foundation, called the Guidelines of Council:

- Speak from the heart.

- Listen from the heart.

- Be lean in your speech.

- Speak spontaneously.

It is always inspiring to hear students bravely voicing their intents to the group, receiving feedback from peers and staff, and wading through the waters of revision.

As a guide, I enjoyed seeing which suggestions students would take and which ones they would not. I loved learning what was most important to them about their own identities and watching them make new self-discoveries in the process. Their intents inspired me.

Like students on Huli Ka’e, everyone participating in the Staff Vision Fast is asked to present their Intent Statement at Intent Council. Going in, I felt good about the time I had spent in drafting my Intent Statement and volunteered to go first.

The questions that came back to me immediately were, of course, “So who are you? And how do you love?” And so the mumbling and fumbling began. I could think of plenty of ways to define myself, but none that I wanted to be defined by. For example:

“Well, I’m a Texan.” Where flowers are purchased from grocery store refrigerators and are systematically chopped off at the roots.

“And I’m queer.” More than anything, though, I believe that love and identity transcend gender and sexual orientation.

“I’m also a writer. And a philosopher. And a teacher. And a student. And an athlete. And a musician. And a sister. And a daughter. And a friend. And a lover. I don’t want to be just one thing.”

“Of course if I had to pick one, I’d pick lover. But that choice has been problematic for me in the past . . .”

I was quiet for a while after that. I didn’t know what else to say. I didn’t have the answer. So I went to my personal tool kit and selected: poetry.

“I’m thinking of a line from Mary Oliver: ‘You do not have to be good.’ I want to believe that line. But I grew up believing that I was a sinner. That I was broken, fundamentally.”

Everyone was waiting on me to say something else, to reach some conclusion. But the only things I felt confident in claiming were the things I am not: I am not perfect; I am not straight; I am not religious; I am not connected to where I am from.

I knew that I did not want to be defined in only negative terms, or as a reaction against other things. But I also didn’t want to claim something that I couldn’t know, couldn’t do, or couldn’t be.

As the group sat in a circle, watching me, I began to think that creating an intent statement was one of those things that I just couldn’t do. It was so much harder to be in the spotlight than in the shadows, to be the one seeking guidance rather than the one giving it. My respect for students at Pacific Quest grew by the second. The silence felt crushing. By this point, I was crying.

“When I was introduced to Eastern philosophy, it was a revelation to me. The idea that humans are fundamentally whole—that changed everything. But I guess I’m realizing that I’m still working on really believing that, on believing that I am fundamentally whole, and on living that way.”

It was a short leap from there to my intent: “I am whole-hearted.” I knew that I had severed from my old paradigm of brokenness years before, but I hadn’t found a way to articulate what my new paradigm was, and I wasn’t really doing much about it.

On the one hand, I felt ashamed that I hadn’t realized this about myself sooner. On the other hand, I knew I was not alone. What brings every student to Pacific Quest and every staff to the fast is essentially the same: the need to change.

Check in next week for the final post in this series!

The Intent Council Door: Part III

In this four part series, Janna Pate explores the Rites of Passage work at Pacific Quest. From “Huli Ka’e,” the Rites of Passage experience that students participate in, to the “Staff Vision Fast,” a unique opportunity for staff to gain personal and professional development and a deeper understanding of this important component of the Pacific …

In this four part series, Janna Pate explores the Rites of Passage work at Pacific Quest. From “Huli Ka’e,” the Rites of Passage experience that students participate in, to the “Staff Vision Fast,” a unique opportunity for staff to gain personal and professional development and a deeper understanding of this important component of the Pacific Quest curriculum. Part I discusses Rites of Passage at Pacific Quest and Part II introduces what we call “Intent Statements “.

By: Janna Pate, Academic Coordinator

When I entered the fast, the Intent Statement I began with was: “I am unafraid of who I am and how I love this world.” This was the statement I brought with me to the group for feedback in a process called Intent Council.

Students at Pacific Quest also participate in Intent Council. This happens during their experience on Huli Ka’e. As a guide and later as a program supervisor, Intent Council was always my favorite group to witness and participate in. It takes a lot of courage to engage in this process.

During Intent Council, students are asked to follow a set of guidelines developed through the work of The Ojai Foundation, called the Guidelines of Council:

It is always inspiring to hear students bravely voicing their intents to the group, receiving feedback from peers and staff, and wading through the waters of revision.

As a guide, I enjoyed seeing which suggestions students would take and which ones they would not. I loved learning what was most important to them about their own identities and watching them make new self-discoveries in the process. Their intents inspired me.

Like students on Huli Ka’e, everyone participating in the Staff Vision Fast is asked to present their Intent Statement at Intent Council. Going in, I felt good about the time I had spent in drafting my Intent Statement and volunteered to go first.

The questions that came back to me immediately were, of course, “So who are you? And how do you love?” And so the mumbling and fumbling began. I could think of plenty of ways to define myself, but none that I wanted to be defined by. For example:

“Well, I’m a Texan.” Where flowers are purchased from grocery store refrigerators and are systematically chopped off at the roots.

“And I’m queer.” More than anything, though, I believe that love and identity transcend gender and sexual orientation.

“I’m also a writer. And a philosopher. And a teacher. And a student. And an athlete. And a musician. And a sister. And a daughter. And a friend. And a lover. I don’t want to be just one thing.”

“Of course if I had to pick one, I’d pick lover. But that choice has been problematic for me in the past . . .”

I was quiet for a while after that. I didn’t know what else to say. I didn’t have the answer. So I went to my personal tool kit and selected: poetry.

“I’m thinking of a line from Mary Oliver: ‘You do not have to be good.’ I want to believe that line. But I grew up believing that I was a sinner. That I was broken, fundamentally.”

Everyone was waiting on me to say something else, to reach some conclusion. But the only things I felt confident in claiming were the things I am not: I am not perfect; I am not straight; I am not religious; I am not connected to where I am from.

I knew that I did not want to be defined in only negative terms, or as a reaction against other things. But I also didn’t want to claim something that I couldn’t know, couldn’t do, or couldn’t be.

As the group sat in a circle, watching me, I began to think that creating an intent statement was one of those things that I just couldn’t do. It was so much harder to be in the spotlight than in the shadows, to be the one seeking guidance rather than the one giving it. My respect for students at Pacific Quest grew by the second. The silence felt crushing. By this point, I was crying.

“When I was introduced to Eastern philosophy, it was a revelation to me. The idea that humans are fundamentally whole—that changed everything. But I guess I’m realizing that I’m still working on really believing that, on believing that I am fundamentally whole, and on living that way.”

It was a short leap from there to my intent: “I am whole-hearted.” I knew that I had severed from my old paradigm of brokenness years before, but I hadn’t found a way to articulate what my new paradigm was, and I wasn’t really doing much about it.

On the one hand, I felt ashamed that I hadn’t realized this about myself sooner. On the other hand, I knew I was not alone. What brings every student to Pacific Quest and every staff to the fast is essentially the same: the need to change.

Check in next week for the final post in this series!

Questions? Call or Text our Admissions Team: 808-937-5806